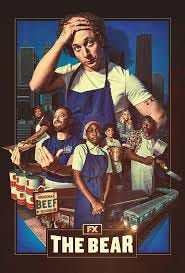

HBO’s The Bear — What It Gets Right and Wrong

Why Chef Life Eats You Alive (and Why We Love It Anyway)

I sit next to my wife watching The Bear, and with every frantic service rush, I see her anxiety coil tighter. Her knuckles whiten, she shifts nervously in her seat. She’s been here before, opening and running a food operation with me, so this is a kind of secondhand trauma. “How the fuck do you put yourself through this?” she asks, disbelief and love tangled in her voice. For me, it’s not anxiety. It’s an old craving — like a recovering addict staring at a cold beer, feeling the rush course through my veins just by imagining it. There’s something exhilarating, something dangerous in that chaos. It’s a rush I know all too well — a rush that nearly broke me but somehow made me who I am.

The irony isn’t lost on me. I swapped the chaos of the kitchen pass for the chaos in my own head, thinking I’d find peace there. Nice try. The truth is, a chef’s service, discipline, madness — it sticks to you. It seeps into your soul. It’s not just a job; it’s a way of seeing, a way of thinking. Underneath all the romance lies a hard, pure reality: we pursue this life because we’re a little mad ourselves. We find peace in pressure, order in the maelstrom.

The Bear could be a mirror of my own story.

Season 1: A high-end chef finds himself stranded in a market stall, then a food truck — swapping foams and sous-vide for a bowl of noodles and the pure simplicity of food made with soul. There’s a Zen in letting the fluff fall away, focusing on what matters: making something honest, without ego. That was me when I left Michelin madness behind and opened a tiny stall in St. George’s Market, Belfast. No tasting menus. No egotistical plated art. Just raw, untamed, soulful food.

Season 2: I opened a small, no-frills ramen joint. It was pure, messy, relentless. No money, and the entire buildout was done by me and my son Tom. A place where a team believed in something bigger than profits. We were a family of misfits, united by the idea that food should nourish, connect, and heal. That a bowl of broth can speak louder than a thousand tasting menus. It wasn’t glamorous; we were making it up as we went, battling health inspectors, unreliable suppliers, and our own doubts. But there was a strange peace in it — a feeling that we were all in it together, shoulder to shoulder against whatever came. We were free.

Season 3: I tried to raise the stakes again. The ambitions, the accolades, the infamous Red Book. I wanted to match myself against the best, to hang my hat alongside those who defined a generation of dining. But the renewal I sought never came. COVID forced me to hang up my whites. My ramen joint — my soul — died a quiet death, without a dramatic last service or toast. It just... slipped away.

After that, I went looking for something in France — redemption, peace, a way forward. I spent time in a 3-Michelin-star kitchen in Bray, hoping to find a spark in a world that felt dimmer by the day. Instead, I found an existential crisis. After nearly eight years sober, I fell off the wagon. The bottle promised an easy oblivion — a temporary peace — but recovery the second time around is a taller, bleaker climb. It forced me to confront myself in ways the kitchen never could. There were no orders to fill, no covers to turn — just me and my doubts.

This is where The Bear nails it: the pressure, the chaos, the battle not just with service but with your own soul. There’s a strange freedom here, a perverse purity. It’s a place where you stare down your doubts, your ego, your deepest disappointments — and somehow, you either emerge on the other side... or you break. The greatest irony? We keep coming back. We keep throwing ourselves into the pressure cooker, not just because we’re mad (well, maybe a little), but because we know there’s something in that suffering — the discipline, the service — that reveals who we truly are.

Two questions I hear the most: “Do you own an air fryer?” The answer is a hard no — I’d sooner boil water in a shoe. And, “How real is The Bear when it comes to professional kitchens?” The answer: very real.

One secret behind that reality is Will Guidara, who took Eleven Madison Park in New York from middling to world’s best. If you haven’t read Unreasonable Hospitality, do it — it’s a masterclass in service. The details in the show — cleaning with a toothpick to reach impossible spots, cutting tape just so, the near-military discipline — that’s not cinematic fluff. It’s the soul of a great restaurant. It’s painstaking, relentless madness. But when you chase it, you become a keeper of something pure.

The show also nails moments when something or someone throws a spanner in the works — like a health inspector arriving mid-service. A standard café might absorb it, offer coffee, show the walk-in, and move on. But in a place like mine — fermenting kombucha in the corner, water-bathing brisket at 58°C for 72 hours — it’s a nightmare. These inspectors work from rules drawn up in the 1980s. So when they see our kitchens, they might as well think we’re cooking meth or anthrax. We scrub, explain, placate — all while trying to keep the service from careening off a cliff.

And then there are the daily disasters: orders shorted, key team members calling in sick or not showing at all. There’s never enough money; you’re always a few covers from going under. You’re the last to get paid if there’s any honey left in the jar at all. Most people will never understand this reality. It’s a constant fight — not against your competition, but against chaos itself. It’s the pressure that either forges you or destroys you. The discipline of choosing, day after day, service after service, to pursue something you love — regardless of the cost.

Owning a restaurant is all-consuming. The feeling you’re always “on,” always responsible — it seeps into your bones. The camaraderie, the friendships, the egos, and the outright shitheads — all become part of the rich, messy road you travel chasing greatness. I’ve spoken to many business owners, and their stories are nearly the same. The main difference? Normal people clock out at five. For us, hospitality is a 24/7 affair. There is no clock. There is no off. There is only service.

Dry your eyes — I’m not complaining. It’s just life. A kind of madness. And it’s that madness that’s so compelling — not just for me but for everyday people. Most want to cook better; some see it as an escape from the dull nine-to-five. But it’s not an escape. It’s hard, tough, joyful, blissful — and it can break your heart or fill it with love in minutes. It’s a paradox — pure chaos and pure discipline — a delicate, dangerous balance.

I see students in my cookery school look at me with hope in their eyes — that naïve spark. They want a piece of it. They want to be called into service when we’re a chef down — to be the hero who saves the day. “Hey, we’re a chef down — can you jump in and save us?” It’s a romantic notion. But the reality is messy, painful, exhilarating — a trial by fire that leaves a permanent mark. There’s deep satisfaction in it, a feeling you’re part of something bigger. But it’s not glamorous. It’s hard, soul-destroying at times. Still, we chase it. Because we love it — or need it.

Another question I get too often: “What’s your favourite thing to cook on your day off?” I picture an accountant asked which Excel sheet he enjoys most. It’s my day off — the best meal is the one I don’t cook. That, or a proper plate of well-cooked food made by someone else who knows their craft. There’s peace in letting someone else care for you. But when I do cook at home, it’s indulgent, rich, unfussy — a perfect medium-rare steak, buttery pomme dauphinoise, or slow-cooked ragu. Pure, simple food — soul food.

Overall, The Bear rings true as a representation of what life in a restaurant chasing stars is really like — the chaos, the discipline, the egos, the friendships, the service. It brings a feeling I can’t fully describe — a rush, a deep recognition. It makes me want to rejoin that struggle. It makes me appreciate my own path — messy, flawed, dramatic — for having lived it. There’s strange peace in seeing it honestly portrayed. It tells me I wasn’t crazy. I wasn’t weak. I was a chef, a warrior in whites — battling service and myself in equal measure.

Because here’s the hidden truth: service is a mirror. Whatever you bring — your doubts, your anxieties, your ego — it reflects back. If you’re weak under pressure, service exposes you. If you’re flawed, service illuminates your flaws in painful detail. But it’s also a path to redemption — a crucible where you confront not just your skill, but your character. To stay, to grow, to conquer — service means conquering something within yourself.

So when I watch The Bear, I’m no passive viewer. I’m a veteran, a fellow soldier. I know the feeling when the first order prints, when the rush begins, when adrenaline surges. I know the silence afterward — when the last plate leaves the pass and you’re left alone with your thoughts: doubts, triumphs, disappointments. And you realise it’s not the accolades you’re chasing. It’s something more elemental. It’s the feeling of having lived through something — together, against all odds. It’s the knowledge you kept going when everything was falling apart.

That’s the madness we choose, again and again.

I've never watched a restaurant or cooking series, but I enjoyed reading you writing about one. I once spent half a year as a dishwasher in a kitchen run by just one chef, who had been there for twenty-five years. That guy was a juggler and an athlete to keep things moving when the place was busy.

Thanks for this, I’ve been dying to know what you’d think of the series. I’m relieved to know it’s realistic - and so interesting to hear the details you share. It does seem such intense pursuits of excellence are more often than not, doomed to “failure” but oh! What the work can do to transform our spirits!